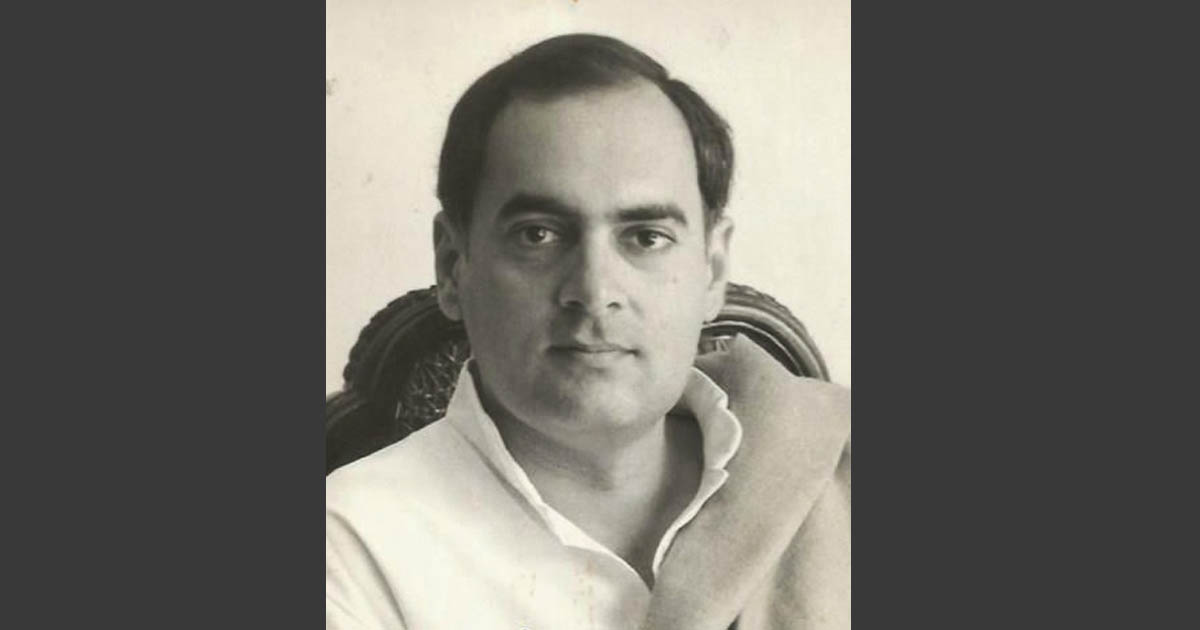

Rajiv Gandhi killing: Thirty-one years since…

Supreme Court sets six of Rajiv Gandhi’s killers free, decades after the dastardly killing

News didn’t creep up on you those days, or shout out of a television set (a tiny black and white thing) which was the privilege of the Editor, whose chamber also had air-conditioning. Instead, it came by lettter, or landline phone, or just shouted out of a telex machine that spewed hundreds of feet of “matter”, a large, electric, extremely noisy hybrid between a dot-matrix printer and a typewriter kind of contraption that had to be kept in a small, separate room. It came in duplicate, with a carbon copy. In times of crisis, the copy would come to the editorial desk while the main print would go the office of the editor.

That day in 1991, the first edition of the newspaper that would travel to across the state was already in print, when a colleague, doing a last minute check before we got into ‘City Edition’ mode shouted ‘Hang on guys, this is big!’. In his hand was a strip of telex printout. ‘Rajiv Gandhi dead’. Agencies call that a ‘Flash’, the first instant bit of news sent to newspaper houses, to alert them. “Rajiv was lying in a pool of blood”. He waited for a few minutes to see if there was some kind of mistake or it was some namesake who had made the news, when the telex coughed into life again, and the gory details flowed in.

In an instant, a place called Sriperembudur became an irreversible part of Indian history, for all the wrong reasons. Rajiv Gandhi who was campaigning at Sriperumbudur in Tamil Nadu during the 1991 elections had been assassinated. Having consulted the editor well past midnight, we called a ‘stop press’. The few thousand copies that had already been printed would be trashed.

Luckily for us, the paper we worked for was pasted ‘modular’, in other words, stories above the fold would end at the fold, so the thing to do was to discard the second half of the front page, bring the top half down and replace the top half with the Rajiv Gandhi story. The chief sub-editor promised me, unilaterally: ‘Get us local quotes and I will give you a byline.’ For a newspaper where bylines were a rarity, that was big. I managed to catch Hiteswar Saikia, who was travelling and get his quote. Also Prafulla Mahanta, in those heady days of Assam politics. One gentleman who never ever won an election and never would, called and gave us his quote. The editions went to print one after the other. I remember walking home, a good 10 km, at dawn with the paper in my hand and my byline on it. The paper didn’t believe that reporters deserved a ride back home; that was the privilege of the ‘page making team on night shift’.

It is perhaps in times such as these that reporters are put to test: hanging around for the edition to be completed way beyond your shift, if reporters ever had one, could suddenly get you the biggest story of your life (a newspaper that always went to bed early not just missed the story but printed a supplement the next day, half a day late!)

As the government set up a special investigation team (SIT) that went after the assassin team, some names would remain etched in Indian memory forever: Dhanu, the human bomb who detonated her RDX belt as she bent down to touch Rajiv Gandhi’s feet, reports said, had calmly watched films the entire day before the assasination. There was a one-eyed Jack called Sivarasan, who in the guise of a reporter would over see the entire operation. They had even carried out a dry run of the assassination to ensure success. Vellupillai Prabhakaran, the chief of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), who had planned out the killing, the chase by the SIT and how some of the assassins who were trapped in a non-descript house couldn’t finally escape. Sivarasan shot himself while the others committed suicide by consuming cyanide. The cyanide capsule that LTTE operatives would wear around their necks would become a mark of one of the bloodiest insurgencies ever.

A lot was to happen after that. Rajiv Gandhi’s family would forgive those who carried out the assassination, they’d be moved by Nalini who begged forgiveness as she was pregnant, and Prabhakaran would eventually be cornered and killed by Sri Lankan forces in 2009. In 1990, meanwhile as militancy hit Assam, and Operation Bajrang was declared, we reporters would once again go about covering blood and gore, this time at home.

Today as six of Rajiv Gandhi’s killers are set free by the Supreme Court, and dozens of ‘in protracted peace talks’ militant leaders walk the streets in Assam, one wonders how this country manages. But it does.

(Photo courtesy Wikipedia, by Government of India)